Multiple lockfiles in Python repos

Photo by Georgia de Lotz / Unsplash

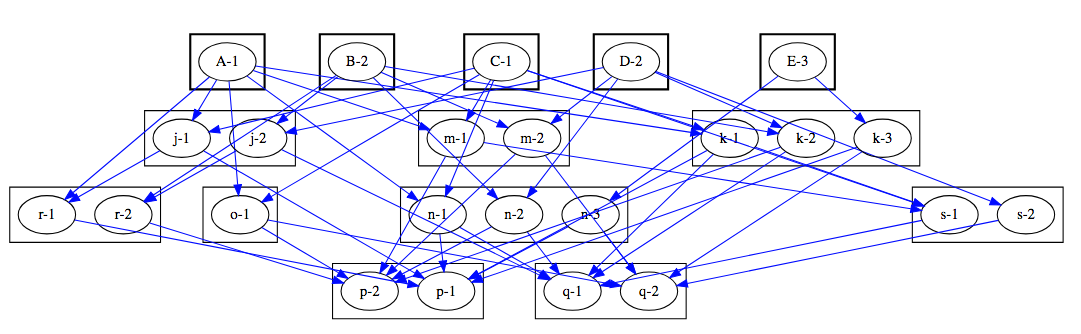

Rather than forcing global or per-project lockfiles, Pants uses a hybrid approach...This allows a repo to operate with the minimum number of lockfiles required to support their conflicting library versions, without necessarily going to the costly extreme of per-project lockfiles.

The Pantsbuild community's top-voted priority from January's 2022 Community Roadmap Survey is our redesign of Python lockfiles. So we were excited to ship in Pants 2.11 support for multiple lockfiles, with a novel hybrid approach.

What's a lockfile?

A lockfile pins every dependency your project installs, including both your direct dependencies and their own dependencies, i.e. "transitive" dependencies.

For example, if your project only uses freezegun, an (abbreviated) lockfile might look like:

{

"locked_requirements": [

{

"artifacts": [

{

"algorithm": "sha256",

"hash": "15103a…",

"url": "https://files.pythonhosted.org/…/freezegun-1.2.1-py3-none-any.whl"

}

],

"project_name": "freezegun",

"version": "1.2.1"

},

{

"artifacts": [

{

"algorithm": "sha256",

"hash": "961d03…",

"url": "https://files.pythonhosted.org/…/python_dateutil-2.8.2-py2.py3-none-any.whl"

}

],

"project_name": "python-dateutil",

"version": "2.8.2"

}

]

}

Why lockfiles?

- Stability: by locking down every dependency, you don't have to worry about waking up to your build breaking because a new version of a dependency was released the night before.

- **Reproducibility:** such as being able to go back to older versions of your project and using the same dependencies as before.

- Security: checksum validation ensures that the artifacts you download are what you expect, reducing the risk of supply chain attacks.

- **Performance:** when installing a lockfile, you only download (in parallel) the pre-chosen versions and artifact URLs. No need to resolve which versions to use.

Multiple Lockfiles

When you only have one project, things are simple: only one set of requirements, and one lockfile.

But what happens when you add a second project, e.g. a second Django project? You have two options:

- Use the same lockfile for both projects.

- Use a distinct lockfile per project.

Typical Python approach: distinct lockfile per project

Several Python tools like Poetry allow you to have one lockfile per project, e.g.:

├── data_science

│ ├── poetry.lock

│ └── pyproject.toml

├── web_app1

│ ├── poetry.lock

│ └── pyproject.toml

└── web_app2

├── poetry.lock

└── pyproject.toml

Often, each project lives in a distinct Git repository, or the "polyrepo" approach. But it's also possible for the distinct projects to live near each other in a "monorepo".

While this approach seems simple at first, teams often run into problems when projects depend on other projects, such as having a common utils project. Projects shared together must have compatible dependencies. When they do not, you typically:

- Update the common project

- Release a new version

- Figure out who all consumers are, then update all consumers to check that they still work. (If any consumer is not using the latest version, you might also have to update them.)

- If any consumers are not compatible, repeat.

- Release a new version of the consumers, and repeat with their consumers. And so on.

One lockfile per project looks simple, but often hides real dependencies between projects: aka "dependency hell."

Dependency hell.

Other downsides of one lockfile per project include:

- Unnecessary maintenance burden and duplication. For example, if you have five Django projects and four of them should still be using Django 3.3, you have to duplicate that version four times, and possibly make sure that they stay compatible with each other.

- Performance hit during dependency installation. You have to install each distinct project, rather than reusing, which can often be slower.

- Not having consistent versions of transitive dependencies across projects, potentially leading to behavior differences in each consumer.

One user described this process as taking multiple developer days in a Poetry-based monorepo (>100 projects) to release a bugfix for a common utility project.

Alternative: single lockfile for everything

Often, the optimal approach is to use only one lockfile for your whole repository. Some benefits can include:

- Simplicity. For example, ensuring that you're using up-to-date dependencies in all projects at once.

- Compatibility. Such as code sharing across multiple projects without worrying about dependency conflicts.

- Performance. You only need to resolve one time to work in the whole repository.

However, you lose flexibility with a single lockfile because every project must be using the same pinned version of dependencies.

Especially as you mix distinct projects in a single monorepo, you may need the flexibility of multiple lockfiles. For example, if one project wants to migrate to Django 4 but the rest of your projects are not yet able to upgrade.

Pants's hybrid approach: granular "resolves"

Rather than forcing global or per-project lockfiles, Pants uses a hybrid approach. Lockfiles are named, and can be used on a per-file basis. This allows a repository to operate with the minimum number of lockfiles required to support their conflicting library versions, without necessarily going to the costly extreme of per-project lockfiles.

First, you define several "resolves", which are logical names for lockfiles.

[python.resolves]

data-science = "3rdparty/data_science.lock"

web-app = "3rdparty/web_app.lock"

Then, you declare which lockfiles (aka "resolves") particular requirements should belong to, if they don't use your default. Pants is able to parse Poetry's pyproject.toml and pip's requirements.txt; often you will tell Pants that that entire file belongs to a particular lockfile. But you can also get more granular, such as declaring a particular requirement to be used in multiple lockfiles.

Finally, you declare which lockfile particular code, tests, binaries etc. should use, if they don't use your default.

pex_binary(

name="app",

entry_point="gunicorn.py",

resolve="web-app",

)

Pants will only infer dependencies on code using the same lockfile. For example, if helpers.py doesn't work with the data-science lockfile, Pants won't let your data_science_app.py file incorrectly use it.

It's possible for requirements and source code to work with multiple lockfiles. For example, you can have a file like utils.py that works with all your lockfiles.

python_sources(

# The files in this folder can be used with both resolves.

resolve=parametrize("data-science", "web-app"),

)

This granularity allows you to have the minimum number of lockfiles necessary, while ergonomically sharing common code across multiple projects.

Trying out Pants

Pants 2.10 added initial support for multiple lockfiles, which was improved in the recently released Pants 2.11.

Try out our example-python repository to see more how lockfile support works, along with other ways Pants improves Python builds like running all your formatters and linters in parallel with caching. And let us know what you think in Slack!